I’m delighted whenever I come across angry adolescent girls acting as protagonists in science fiction and fantasy, because I’ve found it’s not a long list. There are, of course, angry female villains, angry male heroes, and angry male villains of all ages, but I’ve discovered only a relatively few examples of angry young female heroines.

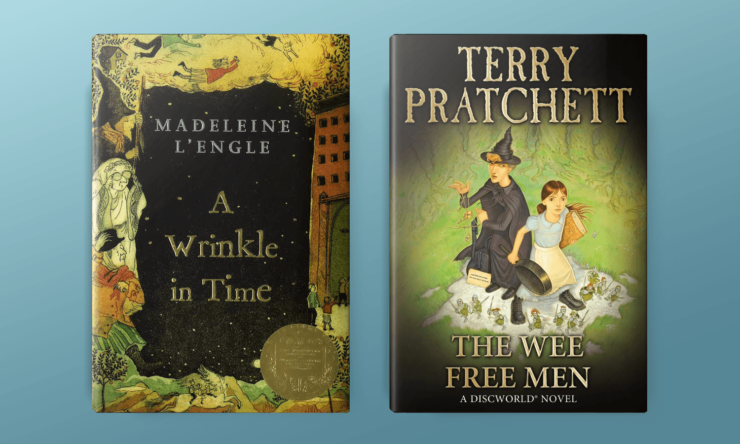

That’s why the similarities between Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time and Terry Pratchett’s The Wee Free Men are so striking. L’Engle’s Meg Murry and Pratchett’s Tiffany Aching both have younger brothers kidnapped by a malignant force, which hinder the boys from being fully human; they both encounter a trio of older women who guide them into a new worldview; they both shoulder the final burden of defeating their story’s villain; and they both are primarily and positively described as angry.

When I first read A Wrinkle in Time as a kid, Meg Murry’s awkward anger was very relatable. Her character is introduced with back-to-back accounts of emotional outbursts: She is sent to the principal’s office, she argues with her classmates, and she punches a bully on her walk home. Each of these angry reactions are prompted by serious issues. The principal makes snide comments about her missing father. Her classmates belittle her. The bully ridicules her younger brother’s assumed mental disabilities. Meg’s anger may be ungainly, but it’s largely justified. Later on the planet Uriel, when Mrs. Whatsit reveals the malignant evil threatening the universe, Meg’s reaction is, again, anger—the shadow is wrong and it should be stopped. Mrs. Whatsit affirms and validates her feelings: “Stay angry, little Meg…You will need all your anger now.” Later, when finally facing IT, the disturbing brain-like villain, Meg resorts to her “greatest faults”: her “anger, impatience, and stubbornness.”

I discovered Pratchett’s Discworld as an adult, but Tiffany Aching’s youthful anger still charmed me. (Tiffany is only nine in her first novel and sixteen in her last, but even at the beginning of her series, she is precocious enough to be grouped with the older Meg Murry.) Tiffany is introduced combatting a destructive magical force armed only with a frying pan and a strong sense of right and wrong. She thinks, “I ought to be scared, but I’m just angry.” As the story progresses, another source of Tiffany’s anger comes to light — anger at her community. There was a harmless old woman cast out on suspicion of witchery, who died as a result. Tiffany boils at the remembrance, knowing that it was vile on two accounts: the woman wasn’t a witch, and more importantly, she didn’t have the means to protect herself. Tiffany recalls her Granny’s belief that “someone has to speak up for them as has no voices.” In the final showdown with the malicious Fairy Queen, Tiffany consistently draws on her anger over the Queen’s injustices to galvanize herself into action. “Ye have murrrder in yer eyes,” observes another character with admiration. Pratchett even goes so far as to note that Tiffany’s “anger rose up, joyfully”—a delightful paradox.

Both girls perceive grave societal wrongs and their response is an anger that leads to action. And yet, the two characters are not perfectly similar, and the two authors do not handle their characters’ anger identically. When Tiffany Aching acts on her anger, it results in plot progress. She defeats the Fairy Queen and decides to become a witch herself because of the communal injustices she’s observed. When Meg Murry acts on her anger, however, it does not positively progress the plot. The first time Meg faces IT is a failure, and immediately afterwards her anger slows the story down. She’s angry at her father for not rescuing her brother. She’s angry at Calvin for siding with her father. She’s angry with the three witches for not defeating IT. We’re told that “all Meg’s faults were uppermost in her now, and they were no longer helping her.” When Meg faces IT again, she’s only able to reach and to rescue Charles Wallace when she abandons her anger to rely on the power of love.

It would be easy to assert that L’Engle was almost progressive in her treatment of Meg Murry’s anger, but that she ultimately failed to fully separate Meg from the more traditionally palatable role assigned to girls and women—the one who heals through love and gentleness. This reading could arguably be bolstered by remembering the criticism L’Engle received upon revealing that Meg eventually forgoes a career in science to become a stay-at-home mom (a decision L’Engle cogently defended, but that still might strike fans as disappointing, particularly for young female readers interested in STEM). After all, L’Engle’s novel came out in 1962. Merely having a female main character be adept at math in a science fiction novel was bold, let alone building a story around an unabashedly angry female main character. Pratchett’s novel came out in 2003—a good 40-year difference, each decade packed with drastic societal shifts in gender expectations. But, on a closer look, dismissing L’Engle’s approach as outdated seems to me like a misreading.

I think anger is tricky because it’s a secondary emotion, a reaction. Avatar: The Last Airbender’s Azula, the Harry Potter series’ Dolores Umbridge, and Game of Thrones’ Cersei Lannister all react with anger when their desire for control is thwarted. Neither their initial desires nor their angry reactions are perceived as admirable. On the other hand, when Mad Max: Fury Road’s Furiosa devolves into a wordless rage at the villain Immortan Joe, turning the tide of the movie’s last violent encounter, her outpouring of anger is rooted in her desire to shepherd other women to a safer existence, free from Immortan Joe’s sexual exploitation. Similarly, Korra, Katara, Toph, and many other female characters in the Avatar series are shown to employ their emotions or anger positively. Anger is multi-faceted, and the determining factor in whether or not it’s considered praiseworthy is often what underlying desire or emotion prompts its expression.

When looking at Meg and Tiffany’s anger, a notable difference amongst the characters’ strong parallels is their sense of self-worth. Tiffany may resent her spoiled little brother for usurping the role of family favorite, but she doesn’t question her own value as a result. She may see herself as slightly outside of her own community, but she doesn’t bemoan the separation as shameful. The awkward Meg, though, laments to her beautiful mother that she is a monster full of bad feeling. She detests herself for being an outsider who hasn’t figured out how to be normal. When Meg’s “hot, protective anger” comes from a place of concern for other people (after observing Calvin’s emotionally abusive home environment, when defending Charles Wallace, or in reaction to the oncoming Shadow), it’s praised. But when Meg’s anger comes from a place of insecurity and shame, it’s critiqued. Aunt Beast remarks: “There is blame going on [in you], and guilt.”

Likewise, we see Meg comforted by those around her in difficult moments through affirmative touch. Calvin and Charles Wallace often reach for her hand. In Meg’s most dire state, Aunt Beast heals her by physically carrying her around like a child. But Meg seems incapable of initiating this kind of physical comfort or reassurance toward others until the end of the book, when she decides to face IT again. Then, Meg wraps her arms around Aunt Beast, declaring that she loves her, and reaches out to her father and Calvin. Unlike Tiffany, who sets out determinedly on a mission to rescue a brother she’s not even sure she likes, Meg first has to learn how to open up and accept her role as part of her community, and manages to do so only after her community continues to reach out to her when she tries to push them away.

It seems, then, that not only did L’Engle praise a female character angered by perceived societal wrongs, but that she also went a step further—L’Engle demonstrated how anger can sometimes be a mask for hurt, and when that is the case, suggests that it should be discarded. I find this to be just as important a concept as righteous, motivating, useful anger. Pratchett does not echo this comparison between types of anger entirely, but he does include a moment when Tiffany’s angry outburst stems from selfish frustration, whereupon she stamps her foot. Tiffany is critiqued at this point by the same character who later admires the murder in her eyes, who encourages her to use her head and advises, “Just don’t stamp your foot and expect the world to do yer biddin’.”

Buy the Book

A Spindle Splintered

We are all familiar with works that insist that adolescent girls are vulnerable or powerless—or only powerful through goodness, purity, and traditionally passive, “feminine” traits and behaviors. These portrayals are common, and in my opinion, objectionable not because they are inherently bad—girls should be allowed to embrace traditional behaviors if they so choose—but because they are too prevalent, with too few positive examples to the contrary. This creates a biased view of what adolescent girls should be, as well as a narrow view of what they can choose to become.

Do both L’Engle’s Meg and Pratchett’s Tiffany fully exemplify this in their stories? I would say yes and no.

To Meg, L’Engle seems to say: you’re different and awkward and sullen now. Don’t worry. Someday you’ll be content and feel beautiful and fit into society like your attractive mother. There is some truth in this statement—young people in general tend to leave behind the angst and terrors of adolescence as they mature into adulthood. But it also glosses over any wrong Meg saw in her community, particularly at school, that contributed to her angry rebellions at the status quo. Even though Meg triumphs over IT, her ineffectuality at home could seem to signal that the story favors eventual resignation towards these ills over acknowledging that an adolescent girl’s perception of right and wrong could produce lasting change. The fact that Meg’s anger isn’t fully resolved shouldn’t be interpreted to mean that the cause of her anger is invalid. There are still injustices and moral wrongs in her community when the novel comes to a close. They simply remained unaddressed for now.

To Tiffany, Pratchett promises: you’re different and special and powerful, and you’ll always be this way—isn’t it glorious to be a witch? Tiffany does occasionally act out wrongly during her series of five books, and has to make amends to her community and her fellow witches. But, nowhere is her anger seen as invalid, only the way in which she handles her anger. Tiffany is emotionally affected by events around her, and her emotional responses prompt her towards successful rectifying actions in the multi-verse at large. But although in later books Pratchett depicts Tiffany using her anger as a propellent toward positive change within her own community, in Wee Free Men, her first novel, Tiffany doesn’t even get credit for rescuing her younger brother, as the patriarchal leaders can’t fathom a girl having managed such a feat.

In the case of both characters, some villains are beaten and some wrongs are righted, and others remain to be faced another day.

I do, though, continue to cherish Meg Murry and Tiffany Aching’s stories for their unique validation of female anger. It’s important to know both that you can rectify a wrong, as Tiffany does when she makes positive changes in her multi-verse and (later) in her home community, and that there are inherent shortcomings to relying on unhealthy anger, as Meg does when she fails to defeat IT and pushes her community away. The two characters embody the positive and productive side of a basic human emotion that is too often met with disapproval or stifled when expressed by adolescent girls, while also demonstrating that girls must be responsible for the outcomes that result from their emotions and actions; in my opinion, that’s a story well worth reading, and taking to heart.

Dorothy Bennett lives with her husband and cat in Austin, where they co-run a video production agency and she works on her first novel. She can be found on Instagram as @dorothy.megan.